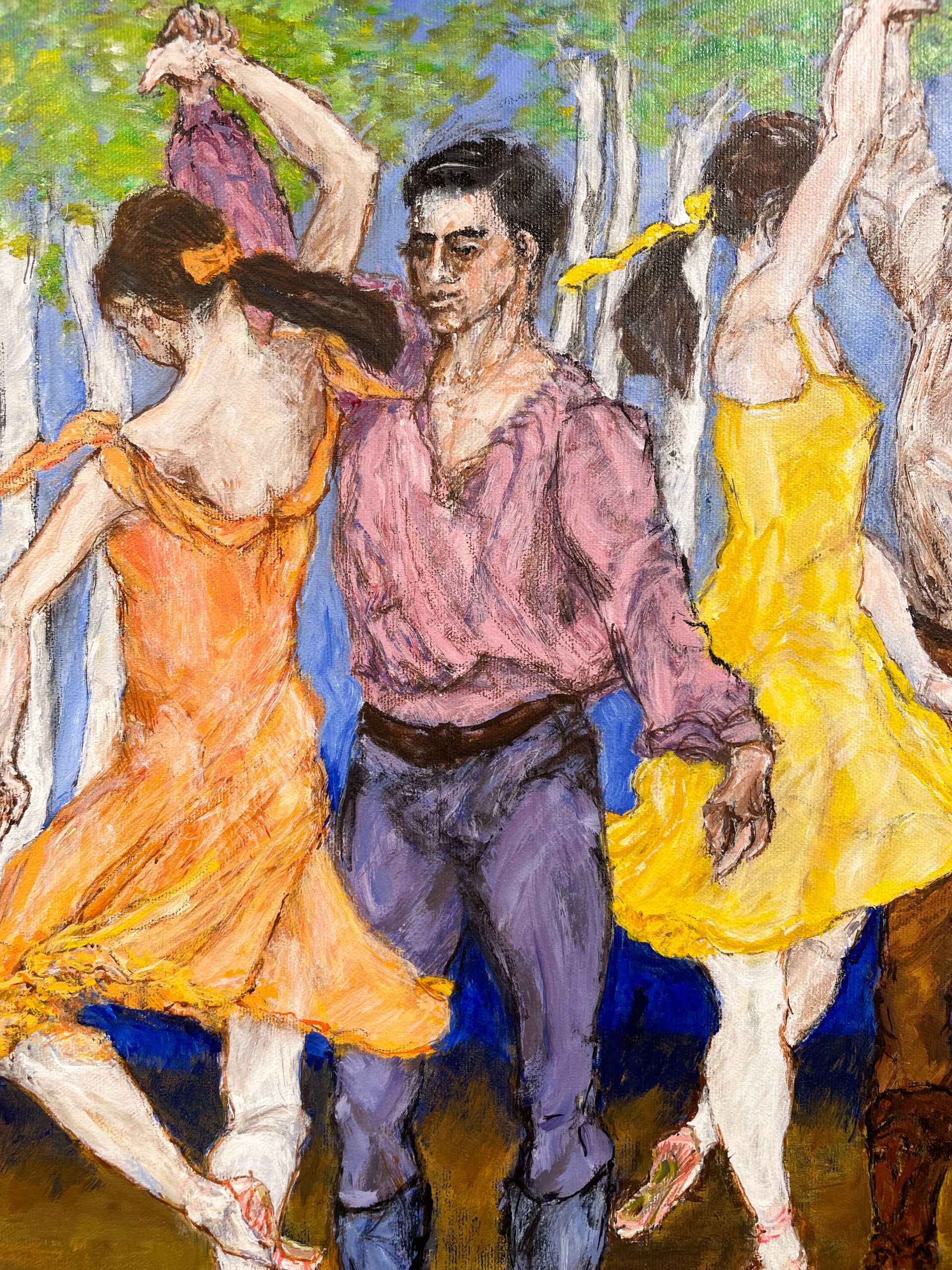

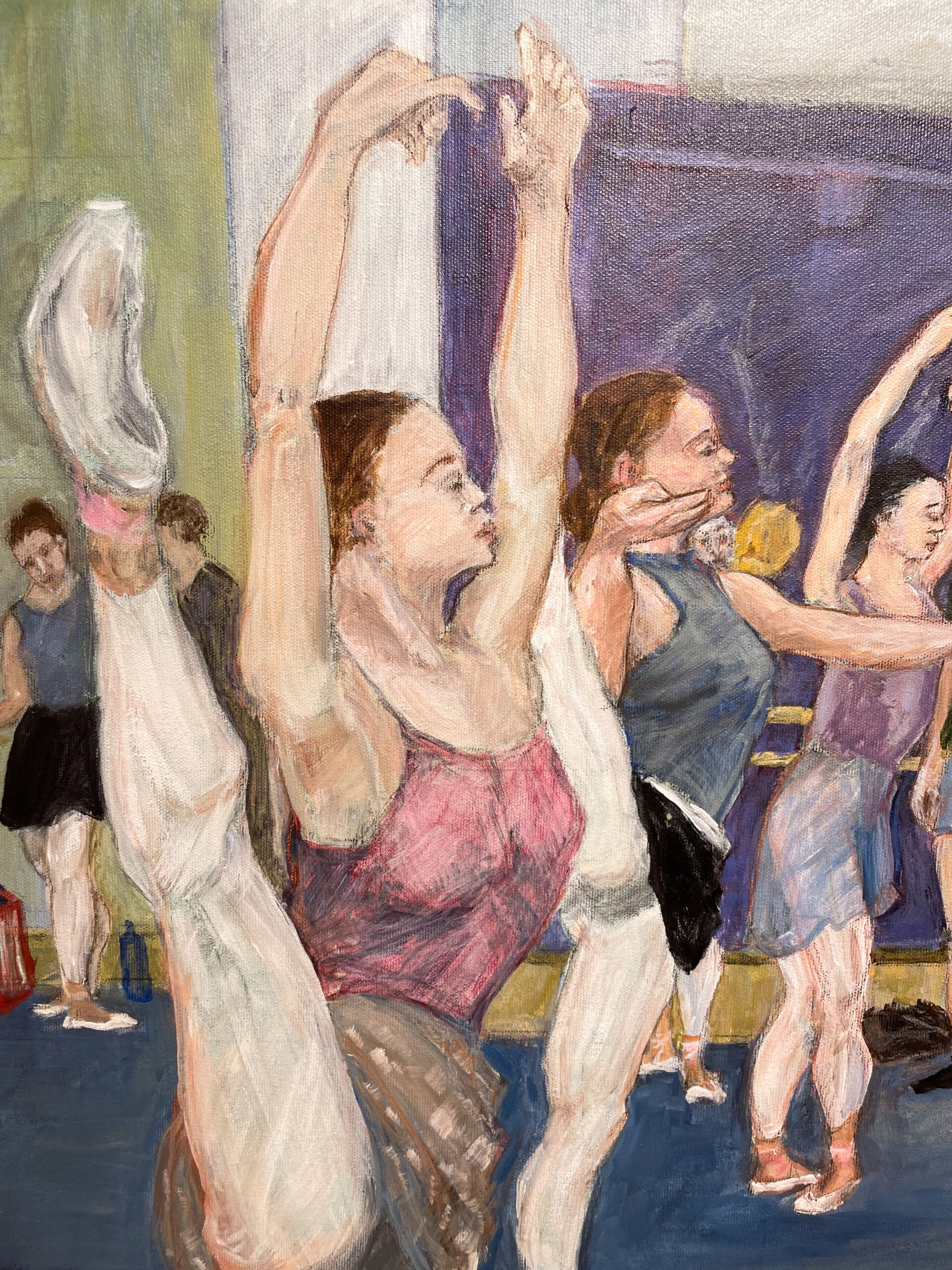

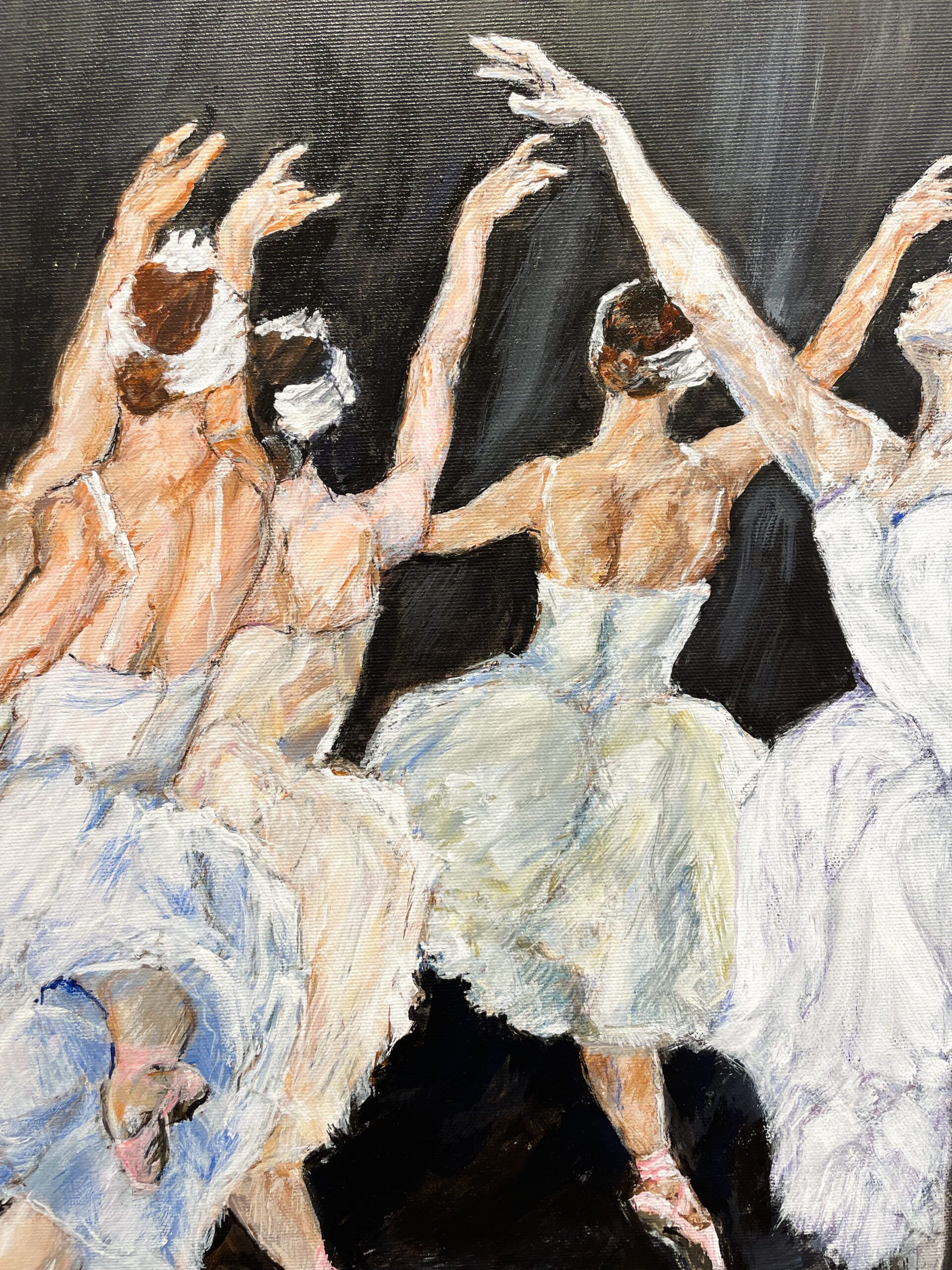

The exploration of Degas’ work and life, for Sandra Flood, combined with her fascination for the world of the contemporary dancer (especially those of the London Royal Opera House) fueled her inspiration for this exhibition. Sandra perfectly captured the movement and magic of ballet and it’s physically demanding practice resulting in her beautiful acrylic paintings capturing the movement of the human body.

“As a painting major at Cardiff College of Art, and Stroud and Cheltenham College of Art, I have always been particularly interested in the human figure. This series of paintings is a homage to the physicality of dancers, to the hours of demanding classes and intense practice to arrive at a polished performance. For me it is also a focused and exciting return to painting and drawing, an ongoing challenge to my technical skills and my ability to capture the movement and magic of ballet.”

Read Sandra’s full story below:

Inspired by Degas

An RVAC members’ exhibition using ‘Inspired by..’ as a jumping off point for a painting or paintings inspired by a renowned painter gave rise to the series “Inspired by Degas”. Maybe Degas was the inspiration to put brush to canvas after some years of avidly watching ballet videos. The Royal Ballet, London, generously puts an enormous number of videos on the web, covering classes, rehearsals, performances, and preparations for performances; introductions to ballets, dancers, choreographers, and behind the scenes personal such as the costume workshops. In fact the whole marvelous, complex range of skills and people that go to put a performance on stage. For me it has been an absorbing journey into another life, and a life-saver during this pandemic. Forbidden travel during lockdown, my usual source of stimulus and inspiration for a new series of work, the Royal Ballet videos have filled that role. Long ago I trained as a painter, and for almost equally as long I have not done any sustained painting, in part because no subject matter drove me to commit it to canvas. Then suddenly I am filled with the urge to paint these amazing dancers, to explore their bodies, their athleticism, the patterns that bodies make working together, the world that dancers inhabit which is so different from what the audience sees.

Edgar Degas: Sources of Information

I have a fellow traveller on this exploration, Edgar Degas (1834 – 1917), a master of paint, pastel and drawing, who studied the dancers of the Paris Opera House for more than four decades. ‘Degas and the Dance’ by Jill De Vonyar and Richard Kendall gives detailed insights into the Paris Opera House and its performances, the dancers and their lives, the cultural milieu in which Degas moved and his involvement with the Paris Opera and the dancers. The authors, a former dancer now a curator, and an art historian who is an acknowledged expert on Degas, dissect his evolving vision of the dancers and the techniques Degas explored in achieving that vision. This reading and other readings on the history of ballet plus prolonged looking at and thinking about Degas’ work in reproduction helped me sort out what Degas actually saw and what he chose to transpose onto canvas or paper and to some extent why.

Degas and Ballet at the Paris Opera

There are recognizable similarities between ballet then and now and there are major differences. Then as now, professional ballet calls for discipline, dedication to a long and strenuous training, and a body and mind that can handle the rigour and uncertain rewards. Paris Opera dancers in Degas’ time trained from an early age, progressing into the company through exams and progressing through the company from corps de ballet to principal through hard work and talent (and occasionally patronage). This is no different from the current members of the Royal Ballet but there are major differences that affect the portrayal of dancers. At the beginning of Degas’ career, female dancers were beginning a move from occasionally dancing en pointe in soft shoes with no support for toes, to some primitive support for increasing en pointe dance, which led to a particular set of exercises for them to strengthen the feet, ankles and legs. Tutus were at least knee to mid-calf length with bloomers worn underneath, and dancers wore corsets that restricted the dancer’s movement of legs and body. All of these reflected French 19th century ideas of modesty and beauty in women. The Paris Opera had banished bravura male dancers, women in travesti played any male roles and in general female dancers were required to glide gracefully through the dance. Many of the ballets were interludes in an extended evening that included a full-length opera.

Degas was a patron of the Opera and, through friends involved with different aspects of the Opera, had access to classes, rehearsals and performances. He also had a studio close to the Opera and, being independently wealthy, was able to hire dancers to pose for him. Dancers move fast, so not surprisingly, the majority of Degas’ dancers are in moments of stasis – resting, adjusting garments, about to move. These male friends and patrons of the Paris Opera, who would have known many of the dancers Degas painted, were also Degas’ primary audience and collectors of his work.

British Ballet

The Paris Opera Ballet has a long and distinctive history deriving from the Court dances of the 16th century. The Royal Opera Ballet has a much more recent history. In Britain at the end of the 19th century, ballet dancers began to appear as part of the mixed bill of music hall acts, a vast commercially organized form of popular entertainment. But it was not until the 1920s and 1930s that ballet attracted the attention of society and its movers and shakers with an influx of dancers from Russian ballet companies performing and setting up dance schools, and the visits of the Ballet Russes with its sets and costumes designed by avant garde Continental artists and its exotic dance themes. Maynard Keynes, the economist, member of the Bloomsbury Group, and husband of a Russian dancer, threw his support as a high-ranking and influential government official behind the nascent London-based companies, amongst which was the precursor to the Royal Ballet directed by Ninette de Valois, an Irish woman. This Company used Russian expertise to reconstruct the classic ballets such as Giselle and Swan Lake, but from the 1930s the Company also started producing ballets in a distinct English style with English themes by British composers and choreographers and with British dancers as their stars. At the end of the Second World War, British ballet and what was to become in 1956 the Royal Ballet Company was seen as the cultural icon of British recovery from the war. Ballet became immensely popular, with principal ballerinas such as the English dancer, Margot Fonteyn becoming as well known as any film star. The Russian ballet companies had never eschewed male dancers, attracting the finest from across Europe, and the British companies followed suit attracting principal male dancers from Europe and training their own male and female dancers at the Company ballet school. The Company over the years has increasingly included dancers of many races. Possibly the principal dancer Carlos Acosta, a Cuban trained dancer of African-Cuban descent was the first pre-eminent coloured dancer in the company.

Using Video

Unlike Degas who was able to watch dancers from a range of view points, including being a member of the audience, my access to ballet has been through video which has limitations dependent on what the camera sees but it also has advantages in that I am able to catch dancers in the fleeting moment of action. I can pause and note exactly the time the action occurs. This is not so simple as it sounds, as dancers move fast and over one second their position can change completely. Even in a seemingly static pose such as Dancer at Rest, the camera catches the dancer moving from wings to sit down, a technician asks if she is OK, the dancer replies and moves away. The moment of repose is no longer than a second. I need to be able to repeatedly catch exactly the same position so that after I have made an initial drawing of the scene, I can come back to it to refresh my memory or add more detail to the drawing.

Degas’ approach

The question of what I am looking for when I watch a video to select a subject for a painting is complex. I have constantly referred to Degas’ paintings and used his titles as an initial guide to subject matter. The results are very different from Degas’, reflecting contemporary practice. Moreover Degas was not particularly interested in painting an exact representation of what he saw but concocted his paintings with drawings made of a single or small groups of dancers combined to suit the demands of his impressionist vision of spacing and colour. Many of the same poses turn up in different guises in numerous paintings and pastels and in reverse in monotypes, often used as a basis for a painting. Degas was interested in the classical dances of the Romantic period and concentrated on the femininity of dancers. Unlike some of his contemporaries painting ballet, he had little interest in the portrayal of interaction between dancers and the admirers looking for sexual favours. Nor did he portray the technical staff or the life behind the stage.

My Working Process

After making a drawing from the video, I square it up and proportionately square up a canvas to enable me to transfer the sketch fairly accurately. I may crop the sketch, add or subtract a dancer, or change the spacing between the dancers. Some of these changes may take place quite late in the development of the painting. Once the sketch is transferred to the canvas, I add areas of thin colour to clarify the dancers’ shapes and positions, and to get an overall idea of the painting. From then on it is a matter of refining, referring to the video for more detail, correcting, redrawing and building up the colour to give the dancers weight and dimension. I am not interested in a photographic portrayal but bodies, hands, feet, and heads have to “feel right”. I hope a dancer would recognize as correct the positions, balance and movement. It is not just the action of the dancers that is important but the emotion the vignette conveys, in Dancer at Rest the exhaustion of a dancer coming into the wings from a very demanding routine, in Dancer Tying her Shoe her total absorption in the task, in Class the concentration of the dancers on the instructor as she demonstrates a series of positions they will be required to perform.

Ballet Today

In more than a century and a half, ballet has changed. Ballets are performed as a full-length program, rather than an interlude in a very long evening of ballet and opera. The audience and patronage has changed along with expectations, the emancipation and earning power of women, and social mores. Male dancers are now an integral part of the company from the corps de ballet to principal dancers. Male dancers change the whole tenor of ballet, both emotionally and physically. Physically, apart from their own bravura choreography, they allow through support and lifts for female dancers an expansion of the possibilities and demands of movement. In fact, ballet has become much more demanding physically, even as support for dancers’ health has become more sophisticated. Dance can now explore the relationships between men and women, both between male and female bodies, emotions and through stories. Versions of the classic ballets from the Romantic period are still performed with mid-calf skirts or tutus, but even the short tutu is considerably more revealing than Victorian mores would have tolerated, as are the tights worn by male dancers. In ballets dealing with historical subjects such as Romeo and Juliet or Mayerling costumes reference the period. In fact, costume designers have become marvelously inventive even in relation to the demands a dancer makes on a costume. What Degas’ reaction to contemporary ballet might be is an interesting question.

Unique Degas

Degas seems to have been unique in his long exploration of the world of the dancer. Some of his younger contemporaries concentrated on somewhat different aspects such as the interactions between wealthy male patrons and young, scantily clad dancers. In the 20th century a few artists continued to paint dancers but they are generally no more than portraits of pretty women in tutus. It seems that no one has since given the world of the dancer the attention that Degas gave it, with the same seriousness, insight, and technical innovation.

- Sandra Flood